By Amar Yumnam

What is all right in Manipur? What draws the public appreciation? What acts as the leading sector of development articulation in Manipur? Nothing, there is nothing. All the planned efforts of India and the consequent interventions in Manipur have not yielded any remarkable display of development transformation. Look at the roads, we still do not have a road infrastructure serving the needs of development as they should be. Look at the water supply scenario, the reality is such that the department responsible for it should be running for cover if it is a responsive one. Look at the power supply scenario, it is still at a very disappointing situation incapable of responding to any development need. The same picture marks the social sector scenario as well. All these have been despite the extension of Indian state’s development policies to Manipur whether or not the policies are alive to the contextual realities of the province. The provincial government too have been busy all along only with the regional implementation of the national programme (effective or ineffective, relevant or irrelevant) and had not had time to articulate and press for the regionally relevant policies alive to the socio-politico-economic realities of Manipur. So the policies have been there on one side and Manipur too has been existing on the other side with no visible and live signs of a connection between policies of the state and lives of the people. The governments have been continuously elected by the people and with no sign yet of the existence of the government for the people.

What is all right in Manipur? What draws the public appreciation? What acts as the leading sector of development articulation in Manipur? Nothing, there is nothing. All the planned efforts of India and the consequent interventions in Manipur have not yielded any remarkable display of development transformation. Look at the roads, we still do not have a road infrastructure serving the needs of development as they should be. Look at the water supply scenario, the reality is such that the department responsible for it should be running for cover if it is a responsive one. Look at the power supply scenario, it is still at a very disappointing situation incapable of responding to any development need. The same picture marks the social sector scenario as well. All these have been despite the extension of Indian state’s development policies to Manipur whether or not the policies are alive to the contextual realities of the province. The provincial government too have been busy all along only with the regional implementation of the national programme (effective or ineffective, relevant or irrelevant) and had not had time to articulate and press for the regionally relevant policies alive to the socio-politico-economic realities of Manipur. So the policies have been there on one side and Manipur too has been existing on the other side with no visible and live signs of a connection between policies of the state and lives of the people. The governments have been continuously elected by the people and with no sign yet of the existence of the government for the people.

But the youths of the province have been proving themselves with louder voices when it comes to sports. The foundation of this is in the traditional strengths of the society and people and not in the policy arena of the government, national or provincial. The disconnect between the policy realm of India and the reality realm of Manipur is to be explained by the differences in ethos, norms, and gender perspectives of the two societies of India at large and Manipur in particular. This disconnect and the lack of contextual appreciation of Indian policy perspective when it comes to Manipur comes out glaringly, though indirectly, in the just published 2012 Global Hunger Index of the International Food Policy Research Institute. The general picture of a very bad scenario of hunger in India established in the latest report is so starkly different from the socio-economic reality of Manipur. But the Indian policy response has been all long to respond to the needs of the larger Indian polity and the implementation at the irrelevant Manipur context ends as one avenue for rent-seeking and corruption.

The Global Hunger Index adopts a multidimensional approach to defining hunger. It “combines three equally weighted indicators in one index: 1. Undernourishment: the proportion of undernourished people as a percentage of the population (reflecting the share of the population with insufficient caloric intake); 2. Child underweight: the proportion of children younger than age five who are underweight (that is, have low weight for their age, reflecting wasting, stunted growth, or both), which is one indicator of child undernutrition; 3. Child mortality: the mortality rate of children younger than age five (partially reflecting the fatal synergy of inadequate caloric intake and unhealthy environments)”. The multidimensional definition takes care of the most vulnerable group of population, children, besides the general population. For children “lack of nutrients leads to a high risk of illness, poor physical and cognitive development, and death. In addition, by combining independently measured indicators, it reduces the effects of random measurement errors.” The countries are ranked from ‘0’ (the best with no undernutrition) to 100 (the worst with all suffering from undernutrition). Compared to 1990, the index has worsened 16 per cent in Sun-Saharan Africa, 26 per cent in South Asia and 35 per cent in the Near East and North Africa. India’s performance on the Global Hunger Index is among the worst in the world. It improved slightly between 1996 and 2001, but by 2012 it has come back to the 1996 level. This indicates that India’s recent economic performance has no positive impact on scores on hunger index. This is in sharp contrast to the global, particularly China’s, positive relationship between economic growth and improvement in the hunger score, Even Bangladesh is far superior to India’s figure. In the case of China, the report writes: “China has lower GHI scores than predicted from its level of economic development. It lowered its levels of hunger and undernutrition through a strong commitment to poverty reduction, nutrition and health interventions, and improved access to safe water, sanitation, and education.” In the case of India, “43.5 percent of children under five are underweight (WHO 2012, based on the 2005–06 National Family Health Survey: this rate accounts for almost two-thirds of the country’s alarmingly high GHI score. According to the latest data on child undernutrition, from 2005–10, India ranked second to last on child underweight out of 129 countries—below Ethiopia, Niger, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Only Timor-Leste had a higher rate of underweight children. By comparison, only 23 percent of children are underweight in Sub-Saharan Africa..” The poor designing and other weaknesses of the Indian policy on such matters are mentioned in the report.

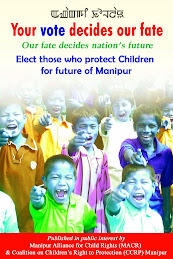

The Indian scenario is something we would never find in Manipur historically and contemporaneously. The three rounds of the National family Health Survey establish this remarkably well. In other words, the children of Manipur are by social tradition are far better taken care than those in the rest of India. This naturally would result in the better performance of Manipuri youths compared to their compatriots elsewhere within the country. This being the case the children and youths of Manipur demand a policy very different from those conceived in Delhi and elsewhere. This is exactly what has not happened in the Indian and Manipur policy making realm.

One policy for children in India is the mid-day scheme for children in schools. While this might have meaning for the children in the rest of India, this does not do so in Manipur. So the mid-day meal policy has practically become a policy for rent-seeking in Manipur. This is what happens in every conceivable national policy in a region where the ethos, norms and happiness are vastly different from the rest of the country where the policies originate.

No comments:

Post a Comment